The Music Of Eric Zeisl

APRIL 2, 2018

Recording session at UCLA Evelyn and Mo Ostin Music Center

JANUARY 7, 2019

Official CD Release on Albany Records

THIS PROJECT WAS GENEROUSLY UNDERWRITTEN BY E. RANDOL AND PAMELA SCHOENBERG, AND WAS PRODUCED AND ENGINEERED BY MULTIPLE GRAMMY AWARD-WINNER FREDERICK VOGLER.

Purchase today from Albany Records

or find us on Amazon!!

Featured Soloists

Michael Sokol

Narrator and Voice of G-d

Mark Kashper

Violin

Repertoire:

JACOB AND RACHEL BALLET

Zeisl’s fourth ballet, Jacob and Rachel, was the result of his collaboration with the famed Russian dancer-choreographer Benjamin Zemach (1902-1997). Zeisl met Zemach while the two were in residence in the late 1940s at the Brandeis-Bardin Institute in Simi Valley, a Jewish arts camp founded by Shlomo Bardin. Zemach had arrived in Los Angeles in 1931 and had produced a number of important dance works, including the 1932 Jacob’s Dream, based on a play by the Austrian-Jewish poet (and distant cousin of Zeisl) Richard Beer-Hofmann. In 1937, Zemach was invited to New York to choreograph the 1937 production of Franz Werfel’s Jewish historical pageant The Eternal Road directed by Max Reinhardt with music by Kurt Weill.

In 1946 Zemach became dance and drama director at the University of Judaism, and it was in this position that he arranged a commission from the New York Arts Foundation for a biblical ballet from Eric Zeisl. The result was the 1953 ballet Naboth’s Vineyard, a powerful, dramatic work based on the biblical story of King Ahab and his scheming wife Jezebel, who instigate the murder of Naboth to obtain his vineyard. Naboth’s Vineyard required a large orchestra, and funds at the University of Judaism were scarce, so Zeisl and Zemach put together a second ballet requiring smaller forces, Jacob and Rachel.

Jacob and Rachel is based on the biblical story of Jacob, who seeks to wed Rachel, daughter of Laban. Laban agrees to part with his daughter only after Jacob works for him for seven years. But Laban tricks Jacob and at the wedding has Jacob marry his older daughter Leah (hidden under a veil). Laban tells Jacob that he must work seven more years to earn the right to marry Rachel. The ballet ends with Jacob agreeing again and consoling Rachel as they listen to the theme of promise.

Unfortunately, the University of Judaism (now called American Jewish University after its 2007 merger with the Brandeis-Bardin Institute) encountered financial difficulties related to moving its location in the 1950s and could not fulfill its promise to premiere either of the two Zeisl-Zemach ballets. Zeisl died in 1959 before either ballet had been performed. The LAJS performance, on May 19, 2009 at the Wadsworth Theater, coming 50 years after his death, was an overdue world premiere.

VARIATIONS ON A SLOVAKIAN THEME

The theme of the Variations is taken from a book of folksongs given to Zeisl by Julius Katay and is called simply Slowakisch. The translation of the text is: Lord God mine, Father mine, give the world your light and justice. Every day your poor servant suffers terribly.

Zeisl originally used the theme and variations as the fourth movement of his First String Quartet (1930). In 1937, he expanded it for string orchestra, which is the version we present tonight.

In describing this movement for the Orel Foundation, Michael Beckerman wrote: “…particularly effective is a Theme and Variations on a Slovak Folksong, revealing everything from the most delicate colors to wild bravura passages; the composer later successfully arranged this for orchestra.”

Notes from Armseelchen: the Life and Music of Eric Zeisl:

The Theme itself, of an abb disposition, fills three five-measure phrases. By composing out the fermatas that separate each phrase, Zeisl produces his second expanding variation. As in the Clavier Trio, tempo markings, character indications, and changes of mode and key impart to each variation such a distinct identity that Paul Pisk’s programmatic designations are amply warranted.

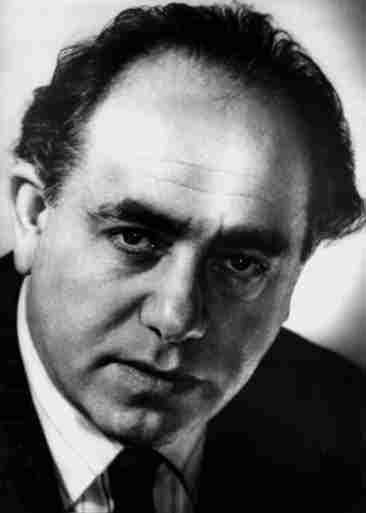

Eric Zeisl

Eric Zeisl was born in Vienna on May 18, 1905. From childhood, he demonstrated an unshakable resolve to compose. Against strong family resistance, he entered the Vienna State Academy at age fourteen. Two years later, his first publication appeared, a set of songs. Zeisl’s music is richly tonal, but with a modern sensibility. UCLA Prof. Malcolm Cole describes his style as “notable for expressive melody, rich harmonies, strong dance-derived rhythms, and imaginative scoring.”

Zeisl was perhaps the youngest of the once successful emigré composers who were forced by the Nazis to abandon their careers and flee Europe. After narrowly escaping capture during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9, 1938, Zeisl and his wife fled from Vienna, settling first in Paris, where Zeisl began his lasting friendship with Darius Milhaud. Upon his arrival in New York at the end of 1939, Zeisl obtained a number of radio performances (and received an unused recommendation from Hanns Eisler for study with Arnold Schoenberg), but he was soon lured to Hollywood, where he suffered from being a late-comer to the movies. He worked on a number of well-known films, but never received a screen credit. He soon abandoned film music and returned to serious composition.

Zeisl was composer-in-residence at the Brandeis-Bardin Institute and at the Huntington Hartford Foundation. At Los Angeles City College, his students included Oscar-winning film composer Jerry Goldsmith and ragtime composer Robin Frost. In Hollywood, Zeisl composed a piano concerto, cello, four ballets, numerous choral and chamber works, and half of an unfinished opera, before being felled by a heart attack after teaching the composition theory class (later taught by Ernst Krenek) at Los Angeles City College on February 18, 1959.

Although much of his music remains undiscovered, Zeisl’s most famous work, the Requiem Ebraico (1945), a setting of the 92nd psalm dedicated to the memory of his father and the other countless victims of the Holocaust, has been performed by major orchestras throughout the world, including performances by the Israel Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (conducted by Zubin Mehta).